Vampires in Halloween

As October starts to come to an end, a mother goes to her child and asks them what they want to be for halloween. What are common answers to these questions? The child may say a princess, a firefighter, a superhero, or more commonly, a vampire. It is not out of the ordinary for a child to want to dress up as a vampire, in fact I think I also dressed up as a vampire at least once when I was a child. Who doesn't want to be a scary blood sucking vampire? Even adults enjoy dressing up as vampires! Its an easy costume, all you need is a cloak, a pair of fangs, and a black outfit, but is that really what a vampire looks like? According to Bram Stoker's Dracula, that description is not quite fitting. He describes Dracula as "...a tall old man, clean shaven save for a long white mustache, and clad in black from head to toe, without a single spec of color about him anywhere." (1).

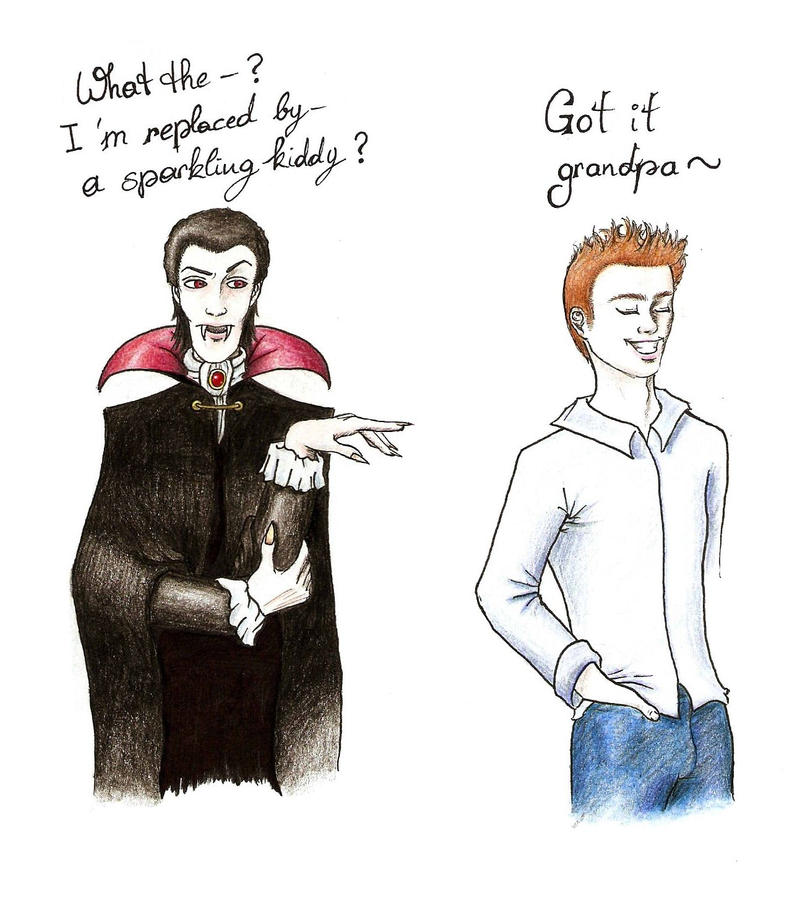

While people may have taken the "clad in black from head to toe"(1) part into play when creating a costume for Dracula, or any vampire, people tend to add a lot more to make it more appealing. For men, they tend to add a long cloak, with the inside being red, and a large popped out collar. They also pair this with a white long sleeve shirt and a red vest. This conflicts the depiction of Dracula in many ways. First it says he was dressed in all black, therefore adding in red and white already makes the costume inaccurate. Also, Dracula was said to be a tall old man, but a lot of young woman and children still seem to dress up as him.

|

| Dracula, as described by Bram Stoker (2) |

|

| Boy Dracula Costume (3) |

Women also take it upon themselves to not only dress as vampires, but to dress up as Dracula. One would think that the costume of Dracula would be intended for only men, since Dracula is a man, but that is not stopping anyone in the 20th century. While you may choose to dress up as any character you like, no matter the gender, the only problem here is the inaccurate portrayal of the character. When women dress up as Dracula they tend to put a sexy twist on the costume. This may have to do with the modern day sexualization of the entities of vampires, or even the sexualization that Bram Stoker showed in his book. Either way, this has lead to women dressing us as Dracula while wearing short black dresses, or long black dresses with high slights and low tops. In some cases these costumes include fishnet tights, and almost always some incorporation of the color red.

|

| "Sexy Countess Dracula" (4) |

1. Stoker, Bram, et al. Dracula. Norton, 1997.

2. villains.fandom.com

3. halloweencostumes4u.com

4. maskworld.com